Plastic, especially recycled plastic, is the subject of numerous contemporary artworks by artists who have made it both an expressive medium of their creativity and a need to communicate its functions and opportunities for reuse. One thinks of Alison McDonald and Annarita Serra, Von Wong or Veronika Richterovà, Mary Croteau and Sayaka Ganz, to name a few.

But it is already with Bruno Munari that we have the theorization of an unprecedented role for plastic and a parallel between packaging and nature that is well suited to the interpretation of its function. In fact, Munari, an Italian artist, designer and writer, “one of the greatest protagonists of art, design and graphics of the 20th century,” as the Treccani Encyclopedia defines him, takes up the relationship between form and function, a cardinal principle of the Bauhaus. According to the Bauhaus, an early 20th century German school of design and architecture, “form follows function,” in other words, form is secondary to function. This holds true as the foundation of design, although in reality it is precisely the in-depth knowledge of the nature of the material that allows it to be used according to its aesthetic, physical and structural characteristics, drawing the best out of it in terms of functionality. Munari states that “The designer tries to construct the object with the same naturalness with which things are formed in nature, he does not insert his personal taste into the design but tries to be objective, he helps the object to form itself by its own means.”

This mode of design, which starts from function and arrives at form, seems to recall directly the principle that guides what we are used to calling “smart design” today: applied to packaging, it is nothing more than design that prioritizes function over aesthetics, though without abandoning it altogether, since smart means intelligent, but with style. And so a smart packaging design is one that achieves these ends:

- Achieve packaging that is minimized in bulk and weight

- Add the right “accessories” so that it can be opened or employed easily

- Save raw material and reuse recycled material

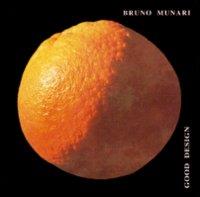

In short, doing what nature does, that is, adapting to evolution by devising an object that will have the shape that best suits its use. And Munari’s genius goes so far as to create a perfect parallel between packaging and what nature produces, applying an “estrangement” effect to the description of an orange that presents its “design” peel as packaging for the fruit it contains in a novel way.

“The whole of these wedges is collected in a package that is well characterized both as a material and as a color: quite hard at the outer surface and covered with a soft inner protective padding between the outside and the container assembly. The material used is all of the same nature originally, but differs appropriately according to function. The opening of the packaging is done very easily, so there is no need for an attached printout with illustrations for use. The padding layer also has the function of creating a neutral zone between the outer surface and the containers so that by breaking the surface, at any point, without the need to calculate the exact thickness of the surface, it is possible to open the packaging and take the containers intact. Each container in turn consists of a plastic film, sufficient to hold the juice, but of course quite maneuverable. A very weak adhesive holds the wedges together so it is easy to break the object down into its various parts all the same. […] The orange then is an almost perfect object where there is absolute consistency between form, function, consumption…”

Equally interesting and amusing is Munari’s description of peas, another perfectly successful example of packaging:

“Food pills of different diameters, packaged in bivalve cases that are very elegant in shape, color, material, semi-transparency and remarkable ease of opening. Both the product itself and the case and adhesive are all derived from a single production source. So not different processes on different materials, to be assembled then at a later stage of finishing, but a very exact work schedule, certainly the result of teamwork.”

There is no doubt that if orange is the perfect packaging, then nature is the world’s greatest designer.